McCarthy's Faust

An essay on Cormac McCarthy's Spenglerian interpretation of the West.

“When I met McCarthy in 2007, he told me that ours is the first civilization to try to get by without a culture. The words stuck with me, but at the time the distinction was not clear to me. What is clear to me now is that he was using the language of Spengler to describe what he sees as our own bad time.”

- Michael Lynn Crews1

“The way of the world is to bloom and to flower and die but in the affairs of men there is no waning and the noon of his expression signals the onset of night. His spirit is exhausted at the peak of its achievement. His meridian is at once his darkening and the evening of his day. He loves games? Let him play for stakes. This you see here, these ruins wondered at by tribes of savages, do you not think that this will be again? Aye. And again. With other people, with other sons.”

- Judge Holden

Literary analyses can be tedious, disjointed, and reaching—so, I’ll begin with two big reaches:

(1) From Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West through The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s novels work as a fictionalized cyclical history of the U.S. BM is the violent, nomad-inspired birth of American culture, which then evolves into the civilization we find sitting uncomfortably in the background throughout the Border Trilogy. This civilization mollifies the driving force behind the nomadic urge expressed by our protagonists John Grady Cole and Billy Parham. Then comes No Country for Old Men, where characters openly lament the degeneration of their lost society. Thereafter American civilization lurches towards winter, and ultimately the seeds of its brilliance (Faustianism) create the ash-filled, post-apocalyptic world of The Road. McCarthy’s Spenglerian interpretation of American history is wrapped up in these six novels.

The second argument is essentially embedded in the first.

(2) A plausible reading Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian places the Glanton Gang as the Aryans reborn in the New World. Look at the language McCarthy deploys, the symbols he uses, and the philosophy espoused by the Judge. Consider the most elementary fact concerning the novel’s structure: the Gang, like the Aryans, moved west with horses and good metal weapons which they used to scratch primitive agrarians from the earth. As the Aryans conquered the Old World, so did the Gang conquer the New World, at least until they ceased their Western, nomadic pursuit, settled down, and tried their hand at commerce.

But, as we’ll see, McCarthy is not a perfect Spenglerian. For McCarthy, the Faustian spirit has been with the West since its birth.

I. McCarthy and Spengler

Admirers of McCarthy’s work should not watch his relatively limited catalog of interviews which mostly concern the nature of consciousness, physics, math, and sometimes modern architecture. Before I saw them, I’d thought of McCarthy more like Thucydides than a (then) living novelist. Now, he’s an impressive autodidact who I watched slump to the intellectual level of his interlocutors, which was as painful with Oprah and as it was with physicist Lawrence Krauss.

But one crucial aside made by McCarthy in the Krauss interview opened a new avenue of appreciation for the author. It went something like this (I’ve spruced it up a bit):

Krauss: Do you think . . . the results of science silence poetry . . . [rambling that inelegantly restates the elegant phrase Krauss just pulled from McCarthy’s The Passenger]?

McCarthy: Well, I think you have to go back to Spengler and, in spite of Spengler being somewhat full of shit, he’s an interesting guy. Somebody said, “You can’t really write him off as a fraud because he’s too smart.” But Spengler understood that science certainly does and probably forever [silences poetry].

Krauss: . . . I’m a huge fan of Shakespeare’s work, but it’s hard to think that it competes, ultimately, with the edifice of the standard model of particle physics. What do you think?

McCarthy: Well, I think Spengler’s right, we’re going to have science after everything else is gone.

Krauss: Interesting . . . Expand on that.

McCarthy: Well, do people seriously believe we still have poetry?

One gets the sense that McCarthy would’ve agreed with Houston Stewart Chamberlain, at least on this point: “Nothing probably is more dangerous for the human race than science without poetry, civilization without culture.”2

Tugging on this McCarthy-Spengler thread a bit more reveals an article written by McCarthy’s associate at the Santa Fe Institute, David Krakauer, who cited some favorable lunch-time discussion topics for anyone interested in picking McCarthy’s brain: “new results in prebiotic chemistry, the nature of autocatalytic sets, pretopological spaces in RNA chemistry, Maxwell’s demon, Darwin’s sea sickness, the twin prime conjecture, logical depth as a model of evolutionary history, Gödel’s dietary habits, the weirdness of Spengler’s Decline of the West, and allometric scaling of the whale brain.”3 McCarthy’s interest in the humanities seems to have evaporated by the publication of his last two novels, but Spengler’s work was still worth engaging. Apparently the long-dead German had been on McCarthy’s mind for some time.

According to Michael Lynn Crews, McCarthy’s notes for Suttree (1979) include references to Spengler4—a significant fact given the order of his post-Suttree novels:

In 1985, Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West, set primarily between 1848-1849, was published.

Then The Border Trilogy, three books set between the 1930s and 1950s.

Next comes No Country for Old Men, set in 1980.

Finally, the post-apocalyptic The Road arrives, which appears to be in the relatively near future.

That’s right. McCarthy devoted the prime of his literary career to putting out novels which run sequentially to one another in time and setting. Somehow, I’ve never encountered a McCarthy reader who’s made this observation. These novels also run a course, beginning with BM and ending with The Road, that proceeds from and bends towards a pre-civilized, nomadic world. Indeed, a resurrected Glanton Gang would’ve fared pretty well in the world described in The Road.

McCarthy and Spengler do, however, disagree on one crucial point related to my both “reaches.”

Spengler’s Decline of the West isn’t much interested in Aryan or pre-historic population movements.5 Further, his stark division between the Classical and the Faustian presents a problem for each proposition. A good Spenglerian’s eyebrows rise at an attempt to find the Faustian soul in Aryan man: “Faustian man was not born on the Steppe,” he’d begin. “Faust is not of the classical or pre-classical world, either. He’s a product of post-Roman Europe. This McCarthy-Spengler connection—this Faust-Aryan connection—it’s all bunk.” Well, perhaps McCarthy had his own opinion on the seeds of Faustianism.

While Spengler divides Western history into the Classical and the Faustian epochs, McCarthy sees the Faustian soul as an ever-present and integral part of what makes the West both uniquely beautiful and hideous—as we’re told, the Gang is “a patrol condemned to ride out some ancient curse.”

II. McCarthy’s Faustianism

It’s a given that McCarthy’s Judge is Faustian. Interesting then is the fact that the core of his philosophy, described in the “War is God” soliloquy, is cribbed from Heraclitus. McCarthy’s personal notes for BM contain the following entry:

War is the father of us all and out [sic] king. War discloses who is godlike and who is a slave and who is a free man. — Heraclitus . . . Let the judge quote this part and without crediting source.6

Helpful here is Michael Lynn Crews’ discussion of McCarthy’s draft of Suttree, which contains a reference to Wyndham Lewis’ scathing criticism of Spengler. Specifically, McCarthy seems to have been working through Lewis’ rejection of Spengler’s view of the “lifelessness” in Classical art.7 For Lewis, McCarthy’s literary output

reject[s] both Spengler’s invidious comparison between classical and romantic (or Faustian) art and Lewis’s equally vociferous partisanship on behalf of classical modes. Both writers rehearse the standard trope of Western criticism of the bifurcation of these two sensibilities, with all the binary oppositions that entails: the spatial versus the temporal, emotion versus reason, static harmony versus kinetic dynamism, to name a few of the ways in which this knife cuts. McCarthy is more interested in these distinctions as poles bracketing a psycho-spiritual continuum. [Emphasis added].

Just as the Faustian Judge “will never die,” McCarthy saw the Faustian spirit as a perennial force carried forward from pre-history into the modern world. If Crews is right, McCarthy seems to have rejected the division Spengler drew between the Classical and Faustian soul. If that’s the case, the inevitable conclusion is that Western man is a product, ultimately, of those who forged the West, the Aryans. As we’ll see, references made throughout BM continuously point the reader back to the pagan world of the those early conquerors and their progeny. We’ll begin by considering the role of the perennial fire in the pre-Christian West, an appropriate starting point given the Judge’s fondness of Heraclitus.

III. The Fire

Consider the bookends of McCarthy’s fictional cycle: the opening of BM and the closing of The Road. In BM, the kid is born in mid-November 1833 under the Leonids meteor shower—one that actually happened, which was so violent that witnesses believed “the world [was] on fire.”8 The kid’s astrological sign is Scorpio, thus he’s “ruled by Mars, a ‘violent planet,’” and also the Roman god of war.9 He is first presented to the reader as a boy in a ragged linen shirt, crouching by a fire—“All history present in that visage.” The kid’s mother dies in childbirth and he thereafter inhabits a world of violent men. In The Road, the boy and the man struggle for survival, but also to “carry the fire.” Just before the father’s death at the end of the novel, he tells his boy that he must “carry the fire”—“It’s inside you. It was always there.”

Fire is a too commonly used metaphor to totally pin down, but I ask you to consider the sacred fire as understood by the ancients of the West:

In the house of every Greek and Roman was an altar; on this altar there had always to be a small quantity of ashes, and a few lighted coals. It was a sacred obligation for the master of every house to keep the fire up night and day. Woe to the house where it was extinguished. Every evening they covered the coals with ashes to prevent them from being entirely consumed. In the morning the first care was to revive this fire with a few twigs. The fire ceased to glow upon the altar only when the entire family had perished; an extinguished hearth, an extinguished family, were synonymous expressions among the ancients.10

Max Müller wrote that the “oldest prayer in the world” was that which the young Brahmin would speak when lighting a fire on his altar at sunrise.11 Swedish Anthropologist Anders Kaliff noted that, in the Indo-European context, “fire united the living and the dead.”12 Thus, when supplied with this historical context, the sentence “All history present in that visage” suddenly carries an even richer, historically rooted context.

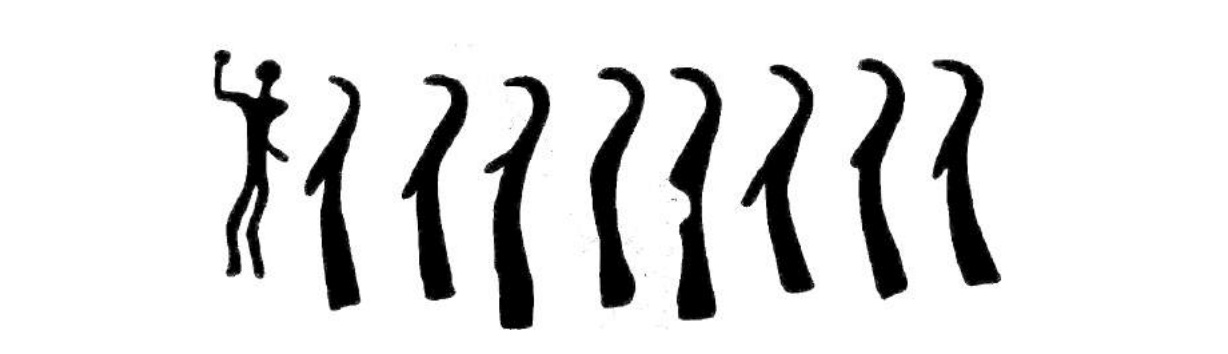

(Recreation of stone carving found at the Kivik (or “King’s Grave”) archeological site in Sweden)

The fire theme is draw-out all across McCarthy’s cycle: consider the epilogues in BM, the Border Trilogy, and No Country:

(1) BM’s epilogue: a man “in the dawn” is moving across the plain, making holes, and “striking fire out of the rock which God has put there.”

(2) The Cities of The Plains’ epilogue: a dream is described to Billy by another man. The dream includes a man who rises from a stone bed in the wilderness to find some ancient tribe offering him a drink from a fire-shapened horn. The drink causes the drinker to forget his pain, but also his past, which appears to causes Billy’s interlocutor to opine as follows: “The world of our fathers resides within us. Ten thousand generations and more. A form without a history has no power to perpetuate itself. What has no past can have no future.”

(3) No Country for Old Men’s epilogue: Sheriff Bell dreams of his father: “we was both back in older times and I was on horseback goin through the mountains of a night. . . . It was cold and there was snow on the ground and he rode past me and kept on going. . . . I seen he was carrying fire in a horn the way people used to do and I could see the horn from the light inside of it. And in the dream I knew that he was going on ahead and that he was fixin to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold . . . .”

McCarthy links fire to lineage, the ancients, and the power of history. In BM we have fire in the dawn and movement, nomadism; in the Border Trilogy, fire is used to transform the object (the horn) which man then uses to forget the past and “the world of our fathers." Finally, in No Country, we see that the fire is still alive, even as the cold winter approaches. As we know, the fire continues on through the civilizational collapse described in the The Road—it’s carried by a father who then passes this sacred responsibility to his son.

IV. BM’s Cyclicity and Further Evidence of Spengler’s Influence

Now we turn directly towards Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West—a title which, as Crews (and others) note, “is nothing short of an homage to Spengler’s Decline of the West.”13

A. Initial Clues: the Title and the Epigraphs

That Blood Meridian is a work of fiction with a deep appreciation for the historical is made immediately obvious to the reader. Pointing us back in the direction of Spengler is BM’s first epigraph, the novel’s very first words:

Your ideas are terrifying and your hearts are faint. Your acts of pity and cruelty are absurd, committed with no calm, as if they were irresistible. Finally, you fear blood more and more. Blood and time.

- Paul Valéry

The quote is taken from Paul Valéry’s “The Yalu,” a discourse contrasting Chinese and European governance. But it also gets at the differences in the spirit or life-force of the Orient and the Occident. Our Mandarin tells his Western friend the following:

For you, intelligence is not one thing among many. You neither prepare nor provide for it, nor protect nor repress nor direct it; you worship it as if it were an omnipotent beast. Every day it devours everything. It would like to put an end to a new state of society every evening. A man intoxicated on it believes his own thoughts are legal decisions.

Valéry’s mandarin contrasts the “intelligence” (really, the Faustianism) of the West with the Chinese’s bounded or restrained intelligence:

We do not wish to know too much. Men's knowledge must not increase endlessly. If it continues to expand, it causes endless trouble, and despairs of itself. If it halts, decadence sets in. . . . we invented gunpowder—but for shooting off fireworks in the evening.

Putting aside the mandarin’s lack of account for the raw barbarity which befalls China whenever a given Emperor’s Mandate of Heaven fades, his observations on the boundless, fearless, and exploratory nature of the Western/Faustian intellect must have appealed to McCarthy. He chose his epigraphs carefully; the fact we are introduced to BM with an epigraph pulled from a story which singles out the uniqueness of the Western intellect—when considered alongside McCarthy’s stated interest in Spengler—is a sign of the centrality of the Faustian vision of the West for McCarthy. Crews agrees and wrote that he found an association between Judge Holden’s appreciation for knowledge as a means to gain tyrannical power over the physical world and the Valéry’s mandarin’s soliloquy.14

Then there is the haunting epigraph McCarthy pulled from a 1982 Yuma Daily Sun article:

Clark, who led last year’s expedition to the Afar region of northern Ethiopia, and UC Berkeley colleague Tim D. White, also said that a re-examination of a 300,000-year-old fossil skull found in the same region earlier shows evidence of having been scalped.

John Sepich thought this epigram “as graphic a statement of the theme of repetition as can be imagined to preface” the novel. I agree and stop to point out his notation of McCarthy’s “repetition,” which we’ll discuss further presently.

B. The Physical Books Itself

The book’s structure points to McCarthy’s cyclical understanding of history: BM shows itself to be a palindrome. Here I turn to Christopher Lee Forbis’ essay “Of Judge Holden’s Hats; or, The Palindrome in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian,” which provides a quite convincing list of identical (or near identical) words or instances found equidistant (or nearly equidistant) from the beginning and end of the book. Here’s a sampling, with mirrored page numbers in parenthesis:

The Leonid meteors (3) are described as the story opens, and the “Stars were falling across the sky myriad and random” on the the kid’s (now the man’s) last night in Fort Griffin (333).

The kid’s mother died giving birth (3), and the judge refers to the kid as “son” (306, 327), and in these inverse relationships is destruction (333-34).

Twice in the book the kid is looked after in upstairs rooms by women (the tavernkeeper’s wife (4), the whore (332), and the word cot only occurs in the novel in these contexts, on these pages.

The word “opinion” occurs only twice in the book and is mirrored (6 / 330).

When the kid comes back to consciousness after their fight, Toadvine asks him, “I said are you quits?” (10), and when the judge first speaks to the man at the Beehive, he asks “Do you believe it’s all over, son?” (327).

The kid witnesses two processions on this set of mirrored pages: he hears guitars and horns, sees men wearing white night shirts (22), to match a procession led by a piping reed and tambourines with “a hooded man in a white robe” (313-14).

Remarkably, a drawing of lots to send men out as scouts during Tobin’s gunpowder story (130-31), mirrors the novel’s lottery of arrows to kill its wounded (205-206).

If you’re not convinced yet, Forbis has got quite the lynchpin:

On the novel’s middle page Holden’s hat is “a panama hat spliced together from two such lesser hat by such painstaking work that the joinery did scarcely show at all” (169).15

This splicing of hats bifurcates the novel perfectly, in its exact middle.

III. Glanton’s Pagans

A. The Prose

McCarthy’s prose in BM is often described as “biblical” (especially in the NKJV sense). But BM is distinctly pagan, especially in its portrayal of the Gang. The members of the Glanton Gang are each some combination of mythological beast out of the pagan pantheon and the early Aryans themselves. They’re “gorgons shambling the wastes of Gondwanaland in a time before nomenclature was and each was all.” They sit around the camp fire “like ghosts . . . rapt, pyrolatrous,”—they’re fire-worshipers, set upon by “some wild thaumaturge out of an atavistic drama.” If the Glanton Gang has a coherent creed, its proselytizer is the Judge—a “great ponderous djinn”—who declares that “if war is not holy man is nothing but antic clay.” Man is therefore grotesque and bizarre, even denatured, when his worship fails to account for making war.

To drive home the pre-Christian nature of McCarthy’s project, consider the mess our protagonist(?), the kid, stumbles into just before joining the Gang, and consider it along side Jesus’ proclamation in Caesarea Philippi: “on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it.”16 The kid enters an abandoned church. Sunlight breaks through the roof and spills onto the western wall; the scalped and partially eaten bodies of Christians lay atop a stone floor, having been murdered by heathens. It was “as if an earthquake had visited.” On the blood-slaked floor “a dead Christ in a glass bier lay broken.” The rock upon which the Church was built was shaken and broken by forces of the Underworld.

Recall too the beheading of the White Jackson. The first conflict the kid witnesses after joining the Gang is between Black Jackson and White Jackson. White tells Black that if he doesn’t get his “black ass away from this fire” he’ll kill him. When White is asked whether that is his final judgement, he says “Final as the judgement of God.” Of course, moments later, Black Jackson takes White’s head with a bowieknife, and two thick ropes of dark blood go “hissing into the fire.” The judgements of God are vacated right from the beginning.

Another obvious example deserves attention: the kid’s encounter with the burning bush after his failure to execute Shelby. Whereas Yahweh spoke to Moses from a burning bush, the kid’s bush is extinguished by the morning and remained silent.

B. The Glaton Gang as Kóryos

The Glanton Gang, like the Aryans, followed the course of the sun, set themselves upon the Amerinds and cleared a path for proper settlers who then built a civilization atop the ruins of vanquished cultures. In the New World, the creation of civilization required Europeans who were willing to revert back to forms of warfare only their earliest ancestors would have known. As T.R. Fehrenbach pointed out, “the wars between civilized whites and barbaric Amerindians were carried out on the same level as the conflicts among the Indians.” This was especially true in Texas and the borderland territory traversed by the Glanton Gang.

The conquest of the Southern Plains required Europeans to draw upon the most barbaric and primitive elements of their being. As demonstrated by the Spanish in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Comanche and Apache could not be subdued using modern European military tactics or technology. Indeed, even the best Amerindian warriors on the Plains, the Comanche, “began to discard muskets and pistols and to rely on their older weapons” right around the time Europeans began arriving from the east.17 As heavily armed Spaniards clunked around New Mexico and Texas in the 18th century looking for pitched battles, the Comanches they were trying to destroy looked more like Mongols than anything the Old World had seen in centuries. As Fehrenbach notes,

“Comanches approached an enemy, whether mounted or on foot, galloping, circling, weaving, each warrior apparently taking no orders from the war chief. The horsemen were never a solid line. They formed a swirling, breaking, dissolving, and grouping mass of separate horses and riders thundering across the prairie, making difficult moving targets. The horsemen charged, broke off before contact, dodged, and weaved. Cannon, which Europeans often used so effectively against massed primitives, was of limited usefulness against such a charge—and so was massed musketry. Such tactics could only be performed by magnificent horsemen, and the net effect sometimes mesmerized the waiting enemy.”

When Anglos-Americans encountered the Comanche—this tribe seemingly plucked from the horse-rich Steppe and dropped atop the Edwards Plateau—it took men like Jack Coffee Hays, the famous Texas Ranger, to revolutionize the way whites fought mounted Amerinds. Hays’ solution was to mimic the the horse barbarians in any way possible. Victor Rose, a 19th century Texan, described the Ranger approach with helpful simplicity: “Make a rapid, noiseless march—strike the foe while he was not on alert—punish him—crush him!” The fifty-year guerilla campaign left many scalpless men rotting in the desert, and though Europe had witnessed its fair share of brutality, the idea of flaying and then burning alive women and children—which the Pehnahterkuh Comanches did in 1839—forced a reevaluation of right and wrong on the Plains. Teddy Roosevelt noted this cultural reversion in his biography of Thomas Hart Benton:

The conquest of Texas should properly be classed with conquests like the North sea-rovers. The virtues and faults alike of the Texas were those of a barbaric age. They were restless, brave, and eager for adventure, excitement, and plunder; they were warlike, resolute, and enterprising; they had all the marks of a young and hardy race, flushed with the pride of strength and self-confidence. On the other hand they showed again and again the barbaric vices of boastfulness, ignorance, and cruelty; and they were utterly careless of the rights of others, looking upon the possessions of all weaker races as simply their natural prey.18

Thus, as Fehrenbach notes, “the Judeo-Christian ethic, Hellenic rationality, and the premises upon which the republic was based provided no rationale for what happened to the Indians.” A Christian society could only reconcile having such men as heroes with great difficulty. The Aryan world, however, would’ve gladly welcomed them.

The Glanton Gang generally steered clear of the most hostile Plans tribes and pulled scalps from the easiest available prey. They were not slaying dragons and at first glance it seems that no worthy mythology would place them as the heroic forgers of a civilization. Similarly, the reality of the Aryan conquests, like those of the countless Steppe tribes which emerge every so often onto the pages of history, looked a lot more like a mass slaughter than what moderns would consider a heroic victory against a worthy foe. But of course, the definition of heroism has not been static. Upon further consideration, perhaps the Gang was not all too different from some of the West’s great heroes.

Early in his masterpiece, Thucydides describes the pirates of early Hellas who would “fall upon a town unprotected by walls . . . and would plunder it.” Moderns might be surprised that “no disgrace” was “attached to such an achievement, but even some glory.”19 Romulus too deserves some attention given the kid’s association with Mars, the Roman God of War. After being suckled by a wolf and fed by a woodpecker, the sacred “bird of Mars,”20 he took up cattle rustling and later drew a following comprised of former slaves and fugitives. Respect for cattle-rustling was hardly unique to Rome. Early Irish kings engaged in an “obligatory cattle raid immediately upon accession.” This was how a new king “prove[d] himself the heroic leader.”21

As Kris Kershaw notes, this is “what ‘war’ was in PIE (proto-Indo-European) times and in the early history of all the daughter peoples. War was razzia: theft of livestock and abduction of women. Even the Trojan war was a large-scale razzia far afield.”22

Now the Glanton Gang begins to look like the ancient Indo-European Kóryos, or Berserkers, or some combination thereof. The Kóryos were young, unwed warriors of the Indo-Europeans and their ancestors. Their historical existence has been located in the myths and rituals of their various descendant cultures. Such a warrior “brakes all connection with his own clan” and is “no longer protected by his people, nor by their law, he at once acquires the right to secure justice for himself.”23 In Greece, they lived on “frontier zones constantly in dispute.”24 These raiders used “stealth and guile” as opposed to numerical superiority; “they were anti-hoplites, guerillas, and they lived and hunted like wolves in the forest.”25 According to Strabo, such men lived “by theft.” Still, they showed “bravery” and a “heroic spirit.”26

The Gang’s mercenary status also deserves attention. They are nomads at work for the governors in northern Mexico, which again brings us to the descendants of our early Aryan nomads. Robert Drews, when describing the rulers of Mesopotamia around the time of Hammurabi (1792 BC), the writes that:

…the nomads were sometimes a threat to a king’s land, and when they caused trouble the king was compelled to drive them back into the wilderness. For such a campaign the king impressed few of his own subjects into military service, because few of them would have made good soldiers. Instead, he turned to other nomadic communities and there found most of the archers, slingers and spearmen he needed.27

Mexican civilians, like Babylonian urbanites, were rather helpless against the nomads who orbited their agrarian settlements, so the rulers employed other nomads for defense.

But of course prolonged contact with civilized society tends to destroy the nomadic impulse. McCarthy’s nomads self-immolate once they become stationary and go into business at the Yuma crossing, as if the very cessation of movement or the overt commercialization of their project psychologically destroyed the gang.

IV. Concluding Thoughts

Blood Meridian will defy any universal interpretation and the argument laid out here is a gesture towards an analysis that would go unmentioned by a careful academic. Doubtlessly, this essay could go on; we could continue to pile references upon references. But I hope the general points presented here suffice to give the devoted reader a new range of appreciation for McCarthy’s work.

Crews, Michael Lynn. Books Are Made Out of Books: A Guide to Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Influences, 307 (footnote 24).

Chamberlain, Houston Stewart. The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, 36.

https://nautil.us/the-cormac-mccarthy-i-know-244893/

Crews, 134-135.

But his nearly indecipherable The Early Days of World History certainly is.

Crews, 107.

Matthew 13:16.

Sepich, 53.

Sepich, 51.

Fustel de Coulanges, Numa Denis. The Ancient City, 29.

Müller, Max. Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illisutrated by the Religions of India, 13.

Kaliff, Anders. Indo-European Fire Rituals, pg 54 (of the PDF available online…)

Crews, 106.

Crews, 176-178

http://www.johnsepich.com/documents/palindrome.pdf.

Matthew 13:16.

Thanks to French traders, guns made it to the Plains long before any settlers.

Roosevelt, American Statesmen: Thomas Hart Benton, 178.

Thucydides, 1.5.

Grimm, Jacob. Teutonic Mythology, Vol. II, 665.

Kershaw, Kris, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the Indo-Germanic, 190, footnote 9.

Kershaw, Kris, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the Indo-Germanic, 22.

Kershaw, Kris, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the Indo-Germanic, 180.

Kershaw, Kris, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the Indo-Germanic, 183.

Kershaw, Kris, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the Indo-Germanic, 187.

Kershaw, Kris, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the Indo-Germanic, 191.

Drews, Robert. Militarism and the Indo-Europeanizing of Europe, 70.